Disclosure Quantified

Published:

This article is also published on Briefly as “Disclosure in Numbers.”

Introduction

I fondly recall my first outround: it started 20 minutes after pairings were posted, and Millburn AW did not disclose. In response to their topical hauntological-feminist-counterfactuals K-aff, I read a disclosure shell and presented reasons why military conscription was a bad policy. Following the crushing defeat, I helped my opponent set up a wiki page.

It’s hard to picture this scene playing out in 2021. Nowadays, my team’s pre-round disclosure decisions mainly concern how to best deflect pesky requests for our new aff’s plan text or standard text. Over my four years in debate, disclosing full-text has gone from unstrategic (because they’ll have your cards!) to even more unstrategic (because they’ll have your cards, and you’ll still lose to o-source!). The change is the product of countless debates over proper disclosure, both in-round and out-of-round.

Much has already been written on the subject. Previous articles have argued that disclosure is more fair and improves clash. Others have responded that disclosure harms creativity, isn’t more fair, and hurts small schools. Follow-up articles have responded that it is more fair, enhances creativity, and protects small schools . Some articles have advocated for full-text disclosure, open-source disclosure, and tournament-required disclosure. The merits of disclosure are even being discussed in Public Forum.

I believe these discussions are too theoretical. Among the articles I referenced, only Bob’s 2014 survey tries to actually assess the state of disclosure in LD. Questions like “does tournament-required disclosure work?” or “do norms improve over time?” benefit tremendously from concrete measurements. So—you guessed it!—I gathered some data.

Before I dive in, I should mention my personal stances. I think disclosure is good. I think open-sourcing might be harmful (for research skills). I’m inclined to favor full-text. You might disagree with me, and this article won’t argue with you. Here, I merely want to present the state of disclosure.

Dataset

I scraped the wikis (during off-hours) of every season starting 2014. Schools and teams with egregiously misformatted wiki pages (i.e. a handful of PF-ers) were omitted. I collected the round info, cite names, and round reports of each team’s page.

I also collected Tabroom data on every LD bid tournament, with historical records reaching back as far as available. Tournaments that weren’t hosted on Tabroom or which didn’t have entries pages were excluded. For the 295 remaining tournaments, I scraped the Novice, JV, and Varsity entries of LD, PF, and Policy. I made some judgement calls in categorizing these, but generally, Novice was open to middle schoolers, Varsity had a TOC bid, and JV was in between the two.[^2]

I matched teams and tournament by using team names and school names. The losses are moderate (think 10%-ish), but significant enough that you should treat the results with caution. The aff and neg pages were combined for the analysis—if they only open-sourced on the aff, that still counts.

The Norm Setters

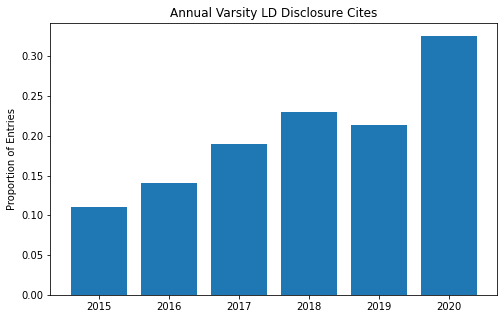

Let’s start with the state of disclosure theory. This season’s debaters love it. About a third of Varsity LD entries had a cite that mentioned disclosure. One-third is huge compared to last season and the season before, when the proportion plateaued at around 20%. It must have to do with the online environment—e-debaters are, on average, more engaged, more tech savvy, and much less likely to just ask for the aff in person.

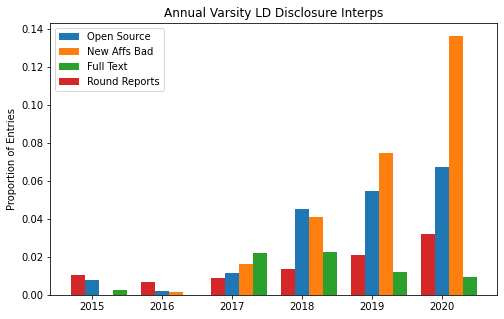

Of course, “disclose citations” isn’t a revolutionary idea. The real changes were in the other disclosure interps: open source, new affs bad, full-text, and round reports. Full-text blew up in 2017 and has steadily declined since; it seems to have been replaced by open source, which is now fairly popular. Round reports is still a fringe interp (as it should be). New affs bad, on the other hand, has grown exponentially: one in every seven debaters demands the plan text!

Norms Have Been Set

Ok, so there’s more disclosure theory—have the sacrifices of substance been worth it?

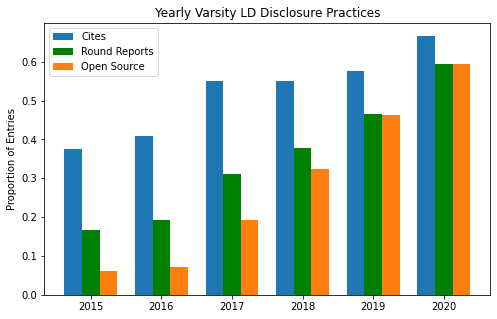

It appears so, and along every metric too. Two-thirds of debaters disclose and the proportion has been growing each year. As we may have expected from the earlier chart, there was a bump in this season of about 10%. Of those who post cites, the share who post round reports and open source has grown consistently since 2016 and now is at almost 90%.

This is remarkable! In 2015, less than 5% of debaters open-sourced. Now, well over half do. The turnaround presents strong evidence that disclosure norms are malleable.

Tournaments

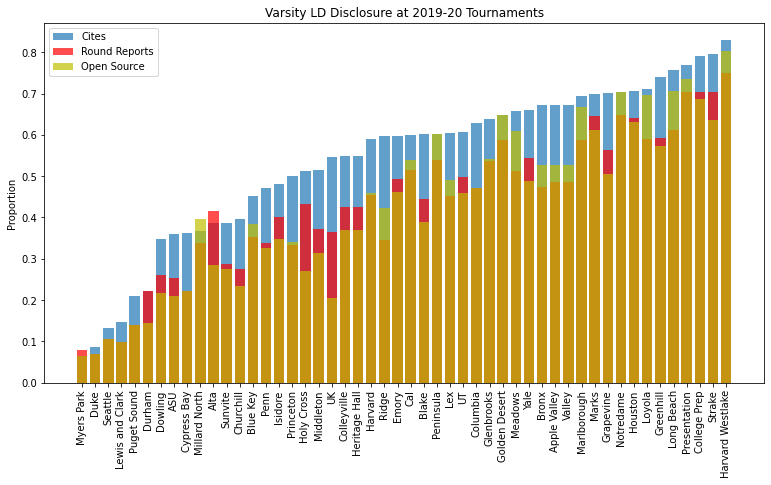

Using Tabroom data, we can disaggregate these rates across tournaments. I looked at just the 2019-2020 season. There’s a ton of variation. Bid-level seems to be the strongest determinant. Sparsely-attended finals bids have the lowest rates of disclosure (e.g. only 4 out of 63 competitors at Myers Park disclosed). Meanwhile, large tournaments in California and Texas tend to lead the pack. A couple east coast tournaments also have strong disclosure practices: Bronx, Yale, and Columbia, to name a few.

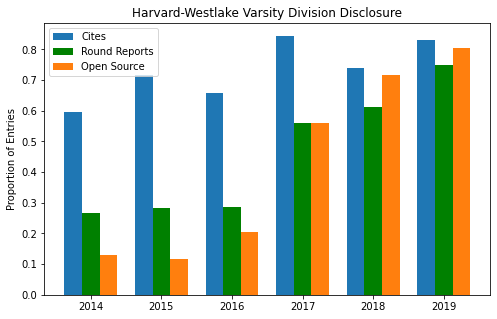

The leading tournament, Harvard-Westlake, is an interesting case study. One reason that they have the highest rates of disclosure is that their invite requires it. That wasn’t always the case. Up until 2016, there was no mention of disclosure in the tournament invite. In 2017, the invite required debaters to post cites. In 2018, the standard was elevated to open source. You can see these changes year-by-year: a big jump in cites in 2017, followed by steady increases in open source in 2018 and 2019.

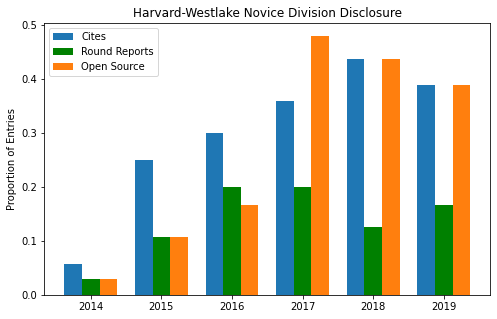

The requirement also applies to the novice division, and the increases here were enormous. The rate of open source nearly tripled from 2016 to 2017, although it has declined since. Cites follow a similar pattern. Make no mistake—these disclosure rates may be lower than those of varsity, but they are stellar compared to the rest of the circuit. You’ll see that in a bit.

All of this suggests that tournament-required disclosure does, in fact, achieve substantial compliance.

But What About the Children?

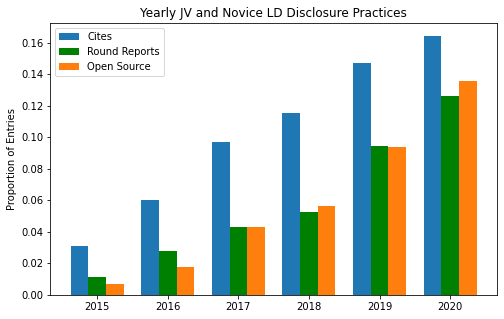

They are learning! From 2015 to 2020, the proportion of novices and JV entries that posted cites increased by six-fold. The rates for round reports and open source increased by eleven-fold and nineteen-fold, respectively.

Of course, the absolute proportion is still very small. If you’re in an average JV or novice division, there’s about a one-sixth chance that your opponent discloses. Nonetheless, if younger debaters are taught to disclose well, that should drive future gains in disclosure practices.

Putting the “Public” in Public Forum

Public Forum is at a tipping point. As PF-ers import arguments from LD and Policy, disclosure has snuck on board. I’ll showcase a few examples here. These wiki pages are from my former high school teammates and they’re fairly representative of the frontier in PF. Their cites certainly aren’t bad (shoutout Dheeraj and Lawrence!).

And when the cites are bad, they open source. I don’t think posting rounds has caught on yet (it’s certainly a hassle), but that’s probably asking for too much, too soon.

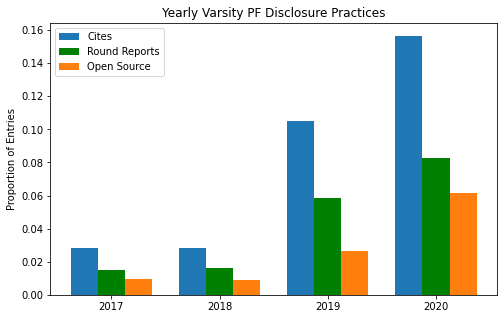

The data bear out these trends. In the first two years of the PF wiki, less than 3% of entries had a wiki. That quickly changed in 2019. Now, Varsity PF debaters post cites more often than JV and Novice LD-ers, and the gap is growing quickly. They’ve also picked up open source. In LD, there was multi-year lag between posting cites and open sourcing; of PFers who disclose, over a third already open source.

If PF takes the route of LD, we can probably expect rapid growth in cites and open source over the next few years, with a small lag in round reports. That will be an interesting development to watch.

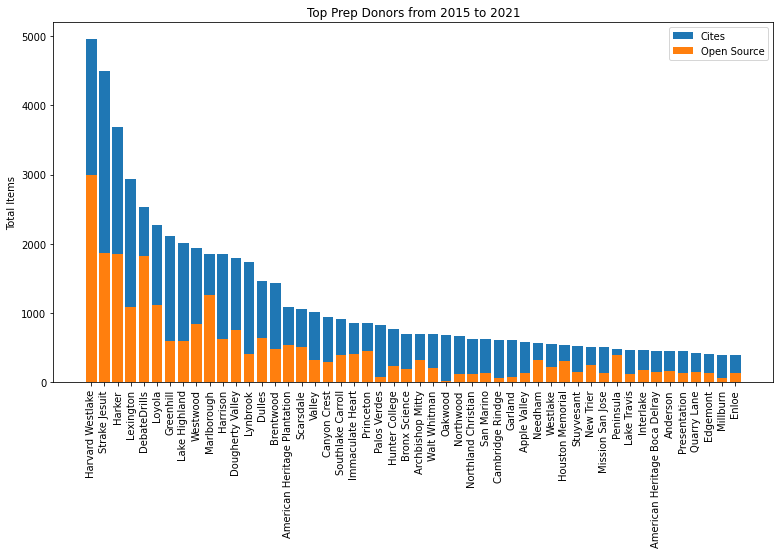

Thank You, Harvard-Westlake

To wrap up, I tallied the number of citations and open sourced documents contributed by each school from 2015 to 2021. They provide crucial sustenance to bottom-feeders like myself in high school. Topping it off with both the most cites and docs is Harvard-Westlake. The runner-ups are Strake, Harker, and Lexington. Just for fun, I included anyone with a “DebateDrills” cite under their own school; very impressively, they came in fifth. Thank you, prep fairies.

Limitations and Next Steps

The data I used were limited in several respects:

- Tabroom data was often unavailable for older tournaments. It seems that larger tournaments were the earliest to adopt Tabroom, which may skew the results.

- I only examined LD bid tournaments, which probably isn’t representative of PF. It certainly would help if someone could collect Tabroom IDs for PF tournaments.

- Some entries were lost in the matching process. If Tabroom said “Harvard-Westlake” and the wiki said “Harvard Westlake” (without the dash), then the entry and debater wouldn’t be connected, which could lead to systematic errors. A softer comparison (that tolerates errors) might do better.

Some cool follow-ups questions that this dataset could help answer include:

- Are successful debaters more likely to disclose? Do they also disclose more?

- Conversely, are debaters who refuse to disclose more likely to win, controlling for other factors?

- What positions are being read? How does that change by location and over time?

- Do debaters “cluster” around types of arguments (e.g. phil, policy, K)? Are judges systemically biased in favor of certain clusters?

Stay tuned. Thanks to Alan George and Joanne Park for their helpful comments on this article. You can find my scraping tools and many more details about the scraping process on the repo. Leave a star! And get in touch if you are interesting in collaborating.