Notes: CS 61C / Machine Structures

Published:

I took these notes for CS 61C: Machine Structures taught by John Wawrzynek and Nicholas Weaver. I highly recommend looking through the solutions to the Fall 2020 final.

Midterm

C

Syntax

0, NULL, and boolean types in stdbool.h are false. Everything else evaluates to true.

Types can’t change. Longs include int, unsigned int, float, double, char, long, and long long. The int is the processor’s integer type. The gaurantee is sizeof(long long) >= sizeof(long) >= sizeof(int) >= sizeof(short). Normally, sizeof(int) = 4.

A const locks in a value. enum lets you group related constants. Function return types can be any C variable.

Bitwise

The C bitwise operators for and, or, xor, and negation are &, |, ^, and ~, respectively. The << and >> operators shift bits left and right, respectively.

Memory

The components of C memory in order from lowest to highest:

- Text segment/code: Read-only executable instructions. Functions are stored in code.

- Static data:

- Initialized data segment: contains global nand static variables, read-write or read-only depending on initialization.

- Uninitialized data segment: Contains all variables that are uninitialized.

- Stack: Stores automatic variables, such as information when a function is called. LIFO. After some area is freed, the values remain, even if they are inaccessible. Not allocated in order.

- Heap: Managed by

malloc,realloc, andfree. Free blocks of memory have headers that store the size of the block and a pointer to the next block. Headers are kept in a circular linked list.

C can dynamically allocate memory.

mallocallocates a block of memory and return a pointer.ptr = (cast-type*) malloc(byte-size);e.g.ptr = (int*) malloc(100 * sizeof(int));Internally, it searches the free list of a large enough block. It can choose blocks via first fit, next fit, or best fit.

callocalso initializes each block with a default value of 0 and accepts 2 parameters.ptr = (cast-type*)calloc(n, element-size);ptr = (float*) calloc(25, sizeof(float));freede-allocates memory.free(ptr);It checks if adjacent blocks are also free and merges them if possible.

reallocallocates more blocks of memory for a pointer.ptr = realloc(ptr, newSize);

If malloc fails, the pointer is set to NULL. Calling realloc on a NULL pointer functions as malloc . Calling realloc(ptr, 0) functions as free(ptr).

When first initialized, pointers point to garbage. Array pointers are located in the same address the array starts.

Anything that takes up memory needs to be freed: strings, lists, structures, etc. Common memory mistakes:

- Returning a pointer a value in a closed function frame.

- Reallocating memory shared by multiple pointers.

freeing the wrong address.- Double

freeing.

Pointers

A pointer contains the address of another variable.

- The general format is

type *var-name; - Usually, pointers are initialized to null.

int *ptr = NULL; - The arithmetic operators are

-,--,+,++ - Pointers will increment in the size of their type.

- Pointers can point to each other.

- Arrays can hold pointers.

- Pointers can be assed into and returned from functions.

Printing

printf accepts a format and arguments. Some formats:

c: characterdori: signed integerf: floating point decimals: stringu: unsigned integerp: pointern: nothing

Struct

Always use

mallocto make space for a new structure.

Use typedef to define new types. For example, typedef uint8_t BYTE;.

To group variables, use struct. The format is: typedef struct { type name; } NAME;

To modify struct members with functions, pass in the address of the object.

Arrays

Create arrays with type[length]. Index to a particular element with array[index]. Keep track of the size:

arr[size] = value;

size += 1;

Array addresses are self-referential.

&arr = arr

Since arrays have fixed length, you may need to reallocate when you reach capacity:

capacity *= 2;

arr = realloc(arr, sizeof(char*) * capacity);

If a string literal is missized with the char array, then the extra space is filled with null.

Strings

String literals (e.g. "Hello World") are static. If a string literal is declared with a char array, it is mutable and sotred in the stack.

To create a new copy of the string, use strcpy(copy_to, copy_from). strlen calculates the length. sizeof will include an extra byte for the terminating null character.

Functions

C is “pass-by-value”, so arguments are copied. First case is almost always NULL case. Use pointers to pass references to objects. As always, multi-part coding problems probably build off of each other, so keep earlier functions handy.

Representations

Two’s Complement

To negate in Two’s complemenet, flip all bits and add 1.

Floating Point

Tricks we use for arithmetic:

- To check for $x == y$, evaluate $x - y == 0$

- To multiply by $2^n$, do left shit by $n$ with

<< n - To divide by $2^n$, right shift by $n$ with

>>n

To represent floating point numbers, use an exponential field to record the whereabouts of the binary point. There is exactly one digit of the mantissa before the binary point. Here are the rules:

- The sign is 1 bit, exponent is 8 bits, and significand is 23 bits.

- The signficand is assumed to start after the floating point.

- The largest and smallest value of the exponent (0, 255) are reserved for special values.

- Exponent 0 and significand 0 is the value 0, which can be positive or negative.

- Exponent 0 otherwise is a denormalized number, which omits the initial 1.

- Exponent 255 with significant 0 is infinity, which can be positive or negative. You recieve infinity by dividing by 0, which can be used for comparisons.

- Exponent 255 otherwise is NaN (not a number). It results from arithmetic with infnities or dividing 0 by 0. Comparisons with NaN are false except for \(NaN \neq x\).

- Due to rounding errors, floating point addition is not associative.

IEC Prefixes

\[2^{10} = \text{Ki}\\ 2^{20} = \text{Mi} \\ 2^{30} = \text{Gi} \\ 2^{40} = \text{Ti} \\ 2^{50} = \text{Pi} \\ 2^{60} = \text{Ei}\]RISC-V

RISC-V is a license-free, royalty-free RISC ISA specification that works with all levels of the computing system. Simply to implement, easy for concurrency, and not many choices. Assembly language operands are registers, which are a limited number of places to hold values. Arithmaetic can only happen on registers, which are very fast.

The processor’s control enables read/write. The datapath lets you read and write data by passing addresses to memory. Access is much faster to register because latency is lower. a program counter is a special register that holds the byte address of the next instructions.

RISC-V has 32 registers with 32 bits each (for RV32; RV16 and RV64 have 16 and 64 bits respectively) referred to as x0 - x31. The x0 register always holds the value 0. Reigsters don’t have a type and the operation decides how values are interpreted. Integers should start on even 4-byte boundaries (“word-aligned”).

There are 6 instruction formats that the hardware understands; they have opcode and operands.

Basic operands

add x1, x2, x3sub x1, x2, x3To move values, do

add x1, x2, x0, sincex0is zero.add x0 x0 x0is the no-op instructionmulandmulhreturns either the lower and upper 32b result, can be fuseddivandrem, can be fused

Immediates are numeric constants

addi x1, x2, 5- There’s no

subibecause you can add a negative number. - An I-type instruction can only have 12 beats of immediate, so immediates are sign-extended.

Load and write

Word addresses are 4 bytes across, so words use the address of their least-significant byte

lw x10, 12(x13)loads the 12th element of the base register atx13tox10s3 x10,40(x13)stores the word atx10to the 12th element of the base registerx13lbandsbcopy a single bit; the extra bits are sign-extendedlb x10, 3(x11)

Logic

and,or, andxorfor boolean operationssllandsrlfor shift left logical and shift right logicalsrais shift right arithmetic, which preserves the sign bit, fails for negative odd numbers- Use

sllito multiply by 4 (useful for byte offsets).

Control flows

beq register1, register2, L1switches to the instructions atL1if the two registers are equalbnebranch not equal,bltbrand less than, andbgebranch greater than or equal are similarbltuandbgeuare unsigned versions- Add label to the code

L1: instruction op1 op2 op3 - Use instruction jump

jto skip to a label, abbreviation forjal. jaladds offset to the curren taddress to the program counter, storing intordthe value of the next instruction.jalrtakes some register value and adds some immediate

Assemblers convert humna-readable assembly code to machine code object files that are linked into an executable.

Some best practices:

a0-a7are for argument registersx10-x17- use

zeroforx0 mv rd, rs=addi rd, rs, 0li rd, 13=addi rd, x0, 13

The steps for calling a function are preparing parameters, transferring control, acquiring local resources, performing the function’s task, storing the result value, and returning to the origin. Registers are either caller saved (the callee can do anything) or callee saved (the funciton must restore them).

a0-a7are used for arguments,a0-a1are for return values (caller saved)- The

rais the address register (caller saved). - The

spis the pointer to the bottom of the stack (callee saved). - `s0-s11 saved registers ar epreserved (callee saved).

- The frame pointer

fppoints to the top of the call frame. t0-t6temporaries are caller saved.- Old values are preserved on a stack in memory which we access with

sp. - The

gpglobal pointer points to static memory.

The R format is register-register arithmetic/logic, I format is register-immediate ALU operations and loads, S format is for stores, B format is for branches, U format is for 20-bit upper immediate instrucitons, and J format is for jumps.

CALL

An interpreter executes other programs. Language translation let’s us translate a high-level language to a lower-level language to increase performance. Generally, interpreters are easier to write, but they are slower. Trasnalated code is almost always more efficient.

A compiler takes high-level language code as input (e.g. foo.c) and outputs assembly level language code (e.g. foo.s), which may contain psuedo-instructions. The lexer turns the input into tokens, while the parser compiles an abstract syntax tree that recognizes problems in program structure. Semantic analysis and optimization checks for errors and reorganizes code. Code generation outputs the assembly code.

An assembler takes assembly language code as input (e.g. foo.s) and outputs object code (e.g. foo.o). It reads and uses directives, replacing psuedo instructions and producing machine language. Directives include .text (put into machine code), .data (put into data segment), globl sym (declares sym global) , string str (stores str in memory with null terminator), .word (stores 32-bit quantities in memory words). Other psuedo instructions include not rd, rs, beqz rs, offset (branch if zero), bgt, j offset, ret, call offset, and tail. Assume function arguments/data structures in C preserve order when transfering to RISC-V.

Branches are PC-relative, so they can be replaced by real ones. Forward references are solved with a first pass to remember label positions. To deal with jumps to other files, a symbol table lists items that the file may need later, whether external labels or pieces of data, and a relocation table lists their locations. An object file is comprised of the object file header, text segment, data segment, relocation information, symbol table, and debugging information.

A linker takes an object code file with information table and outputs executable code (e.g. a.out). It combines several object files into a single executable, enabling separate compilation of files. It combines the text and data segments and fills in absolute addresses by calculating the absolute address from lengths and orderings. PC-relative addressing (beq, bne, jal) never relocates, but external function reference (jal) and static data reference (auipc and addi) always relocate; it checks user symbol tables and library files for an absolute address.

A loader loads the program into memory and runs it. In order, the loader:

- Reads the file header to determine size of segments.

- Creates address aspace for a program and a stack segment.

- Copies instructions and data to the new address space.

- Copies arguments passed into the program on the stack.

- Initializes registers,

sppoints to first free stack location. - Jumps to start-up routine that copies arguments from stack to registeres, sets the PC.

In dynamically linked libraries, libraries are seprate fromt he program, reducing disk pace and send time; but it adds time overhead and complexity.

Summary:

Compiler • Its output may contain pseudoinstructions. • People sometimes do this stage by hand for optimization. • It deals with the syntax of C. • It deals with the semantics (i.e. meaning) of C. • Input file suffix is .c. • Output file suffix is .s

Assembler • Its output is two information tables. • Its input may contain pseudoinstructions. • Its output is true assembly only. • It reads directives. • It replaces pseudoinstructions. • Its output is an object file. • Its output is machine language. • This stage makes two passes over its input. • Input file suffix is .s. • Output file suffix is .o.

Linker • Its input is object code files (among other things). • Its input is information tables (among other things). • Its output is an executable. • One of its jobs is to take the text segments from .o files and concatenate them together. • One of its jobs is to take the code segments from .o files and concatenate them together. • Input file suffix is .o. • Typical output file is a.out. • It is often called the ‘bottleneck’ of the development process. • Its job is to read the relocation table. • Its job is to resolve references and fill in the absolute addresses.

Loader • Its input is executable code. • Its output is a fully running program. • Typical input file is a.out. • This job is typically part of the operating system. • It creates a new address space for the program large enough to hold text and data segments. • It copies instructions into its address space. • It initializes machine registers. • It sets the PC.

SDS

Almost every processor is a synchronous digital system. All operations and communication is coordinated by a central clock. All values are represented by a finite set of values (unlock analog circuits, which represent continuous ranges of values). Wires can take on 0 or 1 values via voltage. Binary representation is reliable and scalable; simply AND, OR, and NOT can represent all discrete functions. Adder logic can be implemented with xor gates

State elements or memory elements gives circuits the ability to remember. They are modeled as finite stat emachines (FSM). cMOS register circuits are edge-triggered, in this case by rising edge of the clock.A bit-register is called a flip-flop. The multiplexor or mux chooses between multiple inputs.

nFET assigns 0 when 1 (bottom up). pFET assigns 1 when 0 (top down). There are physical delays from input to output change. CMOS consume power proportional to the clock frequency.

Final

Datapath and Single-Cycle Control

RISC-V machines execute on instruciton per tick. The program counter points to a place in instruction memory, which fetches instruction components, decodes/reads register, executes the instruction, and writes to memory.

Datapath

Each instruction reads and updates the state. The register files (regfiles) holds 32 registers * 32 bits. The program counter (PC) holds the address of the current instruction. The memory holds instructions (IMEM) and data (DMEM) in a 32-bit byte-addressed space.

At every clock tick, the processor executes an instruction. Current state outputs drive inputs to logic, outputs settle at the values before the next edge. Memory is asynchronouc read but synchronous write.

The phases are instruction fetch, decode/register read, execute in ALU, store in memory, write to registers. Separate inputs select write enable and function choice.

The clk-to-q delay is the time between the clock trigger and the time that the Q output gets updated to a new value. The setup time is how long the input needs to be steady before the clock trigger, and the hold time is how long the input needs to be steady after the clock trigger.

The critical path equation is:

\[T \geq \tau_{\text{clk}\to \text{Q}} + \tau_{\text{CL}} + \tau_{\text{setup time}}\]Minimal clock period questions are about finding the longest path. Maximum hold time questions are about finding the shortest path.

FSM

Sequential circuits with feedback are often modeled as finite state machines, where each cycle the next state is based on the current inputs.

Pipelining

Pipelining can’t improve latency, but it can increase throughput. At any given time, resources are occupied by different instructions. Since the time of each cycle is only limited by the slowest stage, the cycle time is decreased. A common five stage pipeline is IM, Reg, ALU, DM, Reg.

Hazards

A couple types of hazards are possible when pipelining. Structural hazards arise from multiple instructions attempt to use the same physical resource. Multiple ports for each register can enable instructions to read and write simultaneously. Instructions and data memories must be separated, or at least in caches.

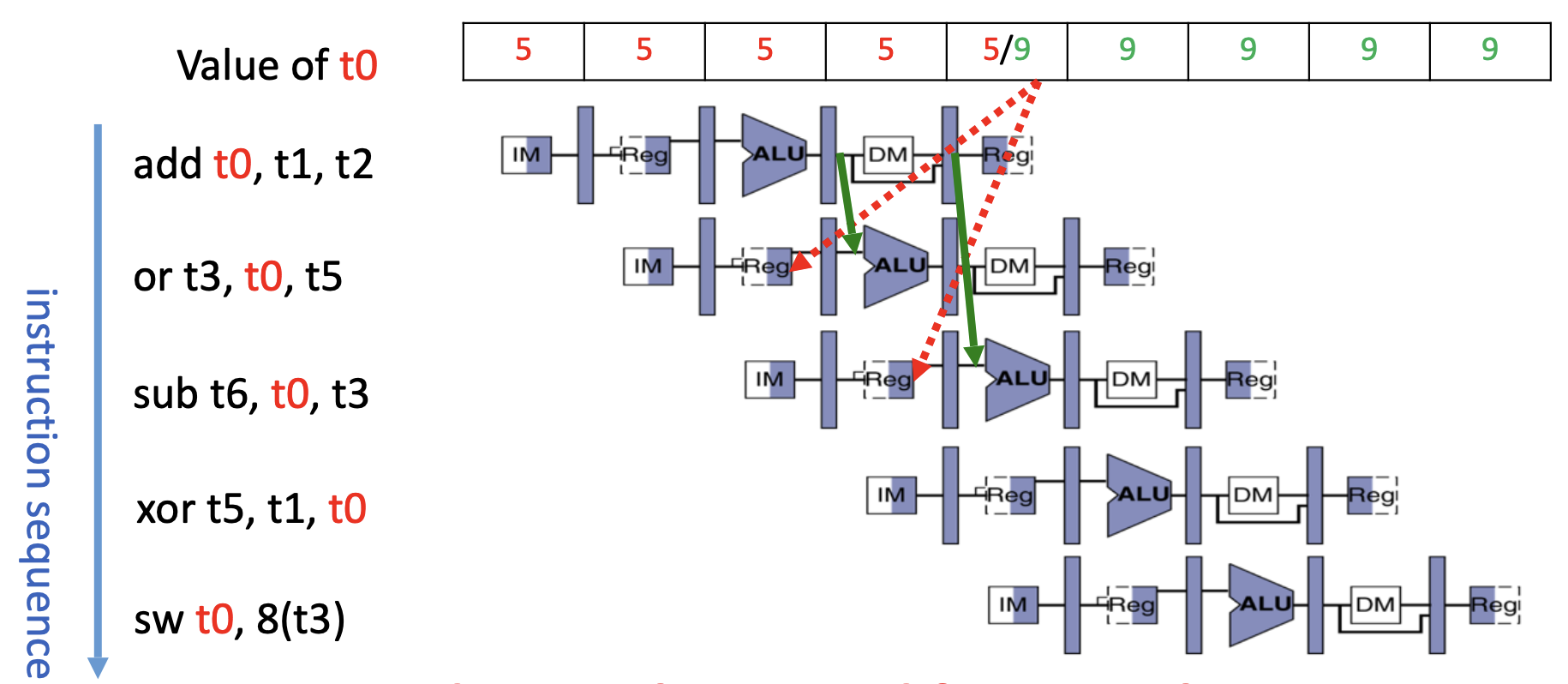

A data hazard can occur in two scenarios. The first occurs when instructions read and write to the same register. Sometimes, the write’s Reg stage will come two cycles after the read instruction’s Reg stage. One solution is to bubble, stalling the dependent instruction. Another is to arrange code in a way to avoid consequetive write/reads. A smart solution is forwarding/bypassing, where the operand is grabbed from the previous pipeline stage when rd and rs1/rs2 indicate a conflict.

With loads, the operand isn’t available until after DMEM, so forwarding requires a bubble.

A control hazard occurs when instructions are executed inspite of an intended branch. A similar solution to forwarding is possible, where if a branch is necessary, mistaken instructions are killed off. A branch prediction cache can improve performance by assuming that branch decisions tend to cluster together.

Superscalars

Superscalar processors create multiple pipeline and rearrange code to achieve greater performance.

Caches

Accesses

Memory accesses tend to occur at the same place and the same time. Instruction fetches, stack access, and data accesses tend to have nice patterns. But pointer chasing when working with objects often makes it impossible to take advantage of locality.

When accessing memory with a cache:

- The processor issues some address.

- The cache checks for a copy of data with that address.

- If it finds a match, it returns it to the processor.

- If it doesn’t, it sends the address to memory. Memory sends the data to the cache, and the cache replaces a word with the new data. The data is sent to the processor.

Blocks of words in a cache are always aligned, so the last two binary digits are always 00 and don’t need to be compared.

Block Size and Associativity

Blocks can be made bigger or smaller. If each block is larger than a word, then part of the address must encode a block offset.

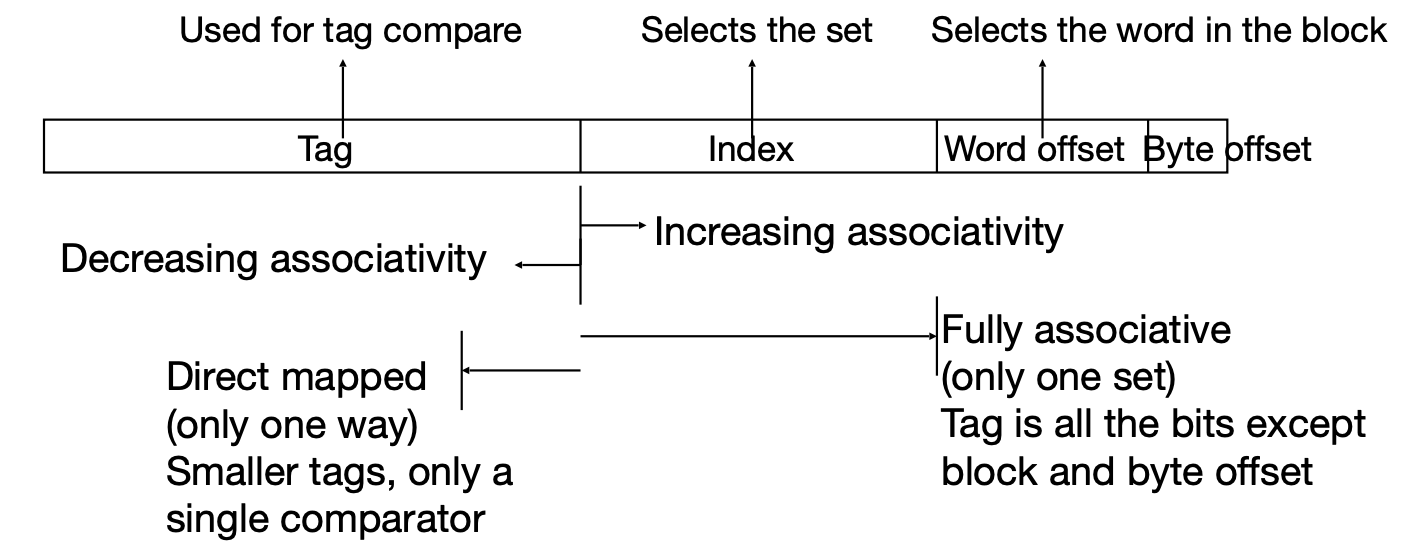

Comparisons are expensive, so tags can be grouped into sets, where bits in the address encode a set number.

The size of index is log2 of the number of sets. The block offset is log2 of number of bytes per block. The size of hte tag is the address size - size of index - block offset.

There are three levels of associativity:

- Fully associative - the block can go anywhere, with no index.

- Direct mapped - each block can go one place, with no tag.

- N-way set associative - with N places for each block.

Handling Stores

There are two policies for cache hits:

- Write-through: write cache and through the cache to memory every time. A write buffer updates memory in parallel to the processor. Simple and reliable, but slower.

- Write-back: write the cache block to memory only when evicted. Blocks have a “dirty” bit that indicates whether if we wrote to the block. Reduces traffic but is more complex.

For cache misses, the data is written to the main memory and may (write allocate) or may not (no write allocate) be written to cache.

Common combinations are:

- Write through and no write allocate

- Write back with write allocate

Eviction

There are two policies for evictions:

- Random replacement - hardware picks random block.

- Least recently used - hardware tracks access history and boots the oldest.

The 3 sources of cache misses are:

- Compulsory: cold start, first reference

- Capacity: cache can’t contain all blocks accessed by the program, solved by an infinite cache

- Conflict/Collision: Multiple memory locations are mapped to the same cache set, misses that would’ve been avoided with a fully associative cache.

Multilevel Caches

Caches can be combined to reduce miss penalty. The global miss rate is the fraction of references that miss some level of a multilevel cache, while a local miss rate is specific to a level.

Performance

The hit rate is the fraction of accesses that hit the cache. The miss rate is 1 - hit rate. The miss penalty is the time to replace a block in a lower level of memory. The hit time is the time to access cache memory. The average memory access time (AMAT) is time for a hit + miss rate * miss penalty.

The cache capacity is associativity times # of sets times block size. The number of cache lines is associativity times # of sets.

Cache design attempts to reduce the time to hit the cache, the miss rate, and the miss penalty. Higher associativity increases hit time, decreases miss rate, and doesn’t affect miss penalty. Higher entries increases hit time, decreases the miss rate, and leaves miss penalty unchanged. Increasing block size doesn’t affect hit time, increases miss rate in the long term, and doesn’t affect miss penalty.

Striding accesses (accessing every i-th element) is designed to break caches. If the strade * sizeof(int) = block_size, then only a single entry in each cache line is used.

Sometimes, an array doesn’t fit inside the cache. If, in a nested loop, both arrays don’t fit in the list, one solution is to block off both for loop’s iterations.

Exceeding capacity is so costly that sometimes a 64-entry victim cache is used to store recently evicted blocks.

When multiple processors are writing the same data, we want coherence, which means that if processor A writes to memory location L, within time T, all other processors will see the updated data. Processor A will broadcast to the other processor that it is writing L, telling them to invalidate the entry in their cache with the dirty bit.

A coherence miss occurs when two processes access the same data. Some multiprocessors use a shared cache to avoid the problem. A proper program structure can also avoid the issue.

Operating Systems

Sharing

The operating system mediates interactions between programs and with the outside world. The OS also gives each process isolation…

- Sharing time via context switching

- Sharing space via virtual memory

Hardware translates virtual addresses into physical addresses, establishes protection and privileges, and enables traps and interrupts.

• The OS is considered more trusted than the user level. • The user can request the OS to do certain operations through syscalls. • The OS is usually trusted. • The OS uses the same virtual memory space as the user does. • The OS has access to the same physical memory space as the user does. • It can be responsible for VA to PA translation.

Traps and Interrupts

Control and status registers are special registers that enforce privileges. An interrupt is caused by something external to the current progrma. An exception is caused by something during the execution of a program. A trap is the act of servicing an interrupt or exception.

Trap handling involves completion of instructions before the exception, a flush of current instructions, a trap handler, and optional return to the code. The hardware adjusts to supervisor mode when handling a trap, saving all the registers. An interrupt is expensive because it trashes the cache.

Context Switching

With the timer interrupt, a processor can run multiple programs simultaneously. A similar strategy works for IO devices, which usually have a devoted section of memory. Since I/O devices run at different rates than the processor, the processor can “poll” I/O devices for data. The alternative to polling is interrupts, where an I/O devices interrupts the current program whenever necessary. Interrupts can be faster when there is little to no I/O.

Polling: • Always causes overall lower latency. • Allows for “always-busy” devices to continuously send input. • Deterministic response time per event. • Used to send checksum packets.

Interrupts: • Preferred for devices that require less frequent servicing by the CPU. • Requires the device to signal for CPU to handle input. • Higher latency per event. • Frees up CPU for other events when no event is in progress.

Direct memory access (DMA) for I/O devices means the CPU only has to initiate data transfers.

Disks & Networks

Solid state drives are much faster than disks because there’s much lower seek time.

Networks rely on links to connect routers and switches. Shared nodes are one-at-a-time, while switches accomodate pairs. The payload of a message is surrounded by header and trailer. Protocols are package structures/control commands that manage communication. TCP/IP gaurantees reliable, in-order delivery and is widely used.

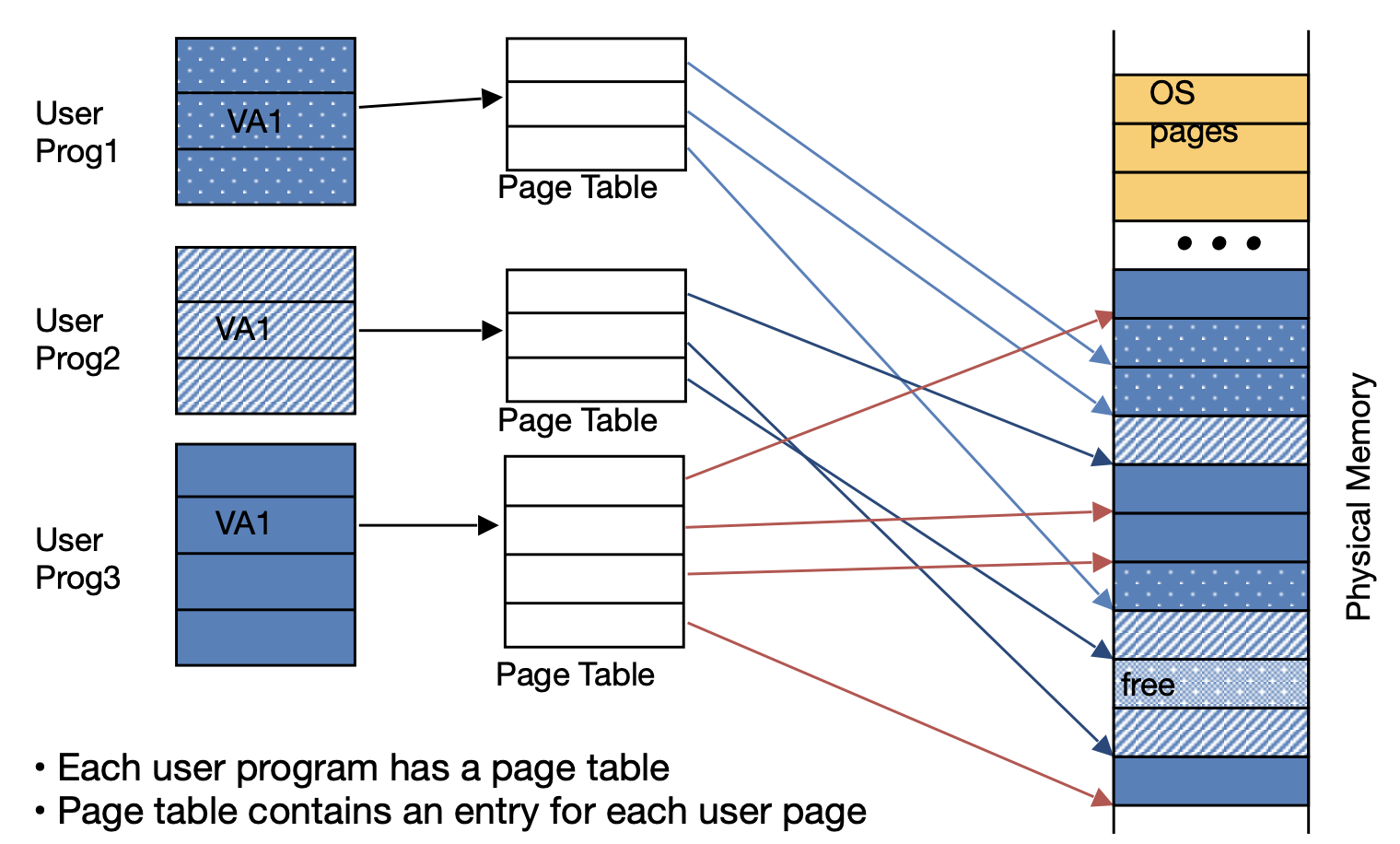

Virtual Memory

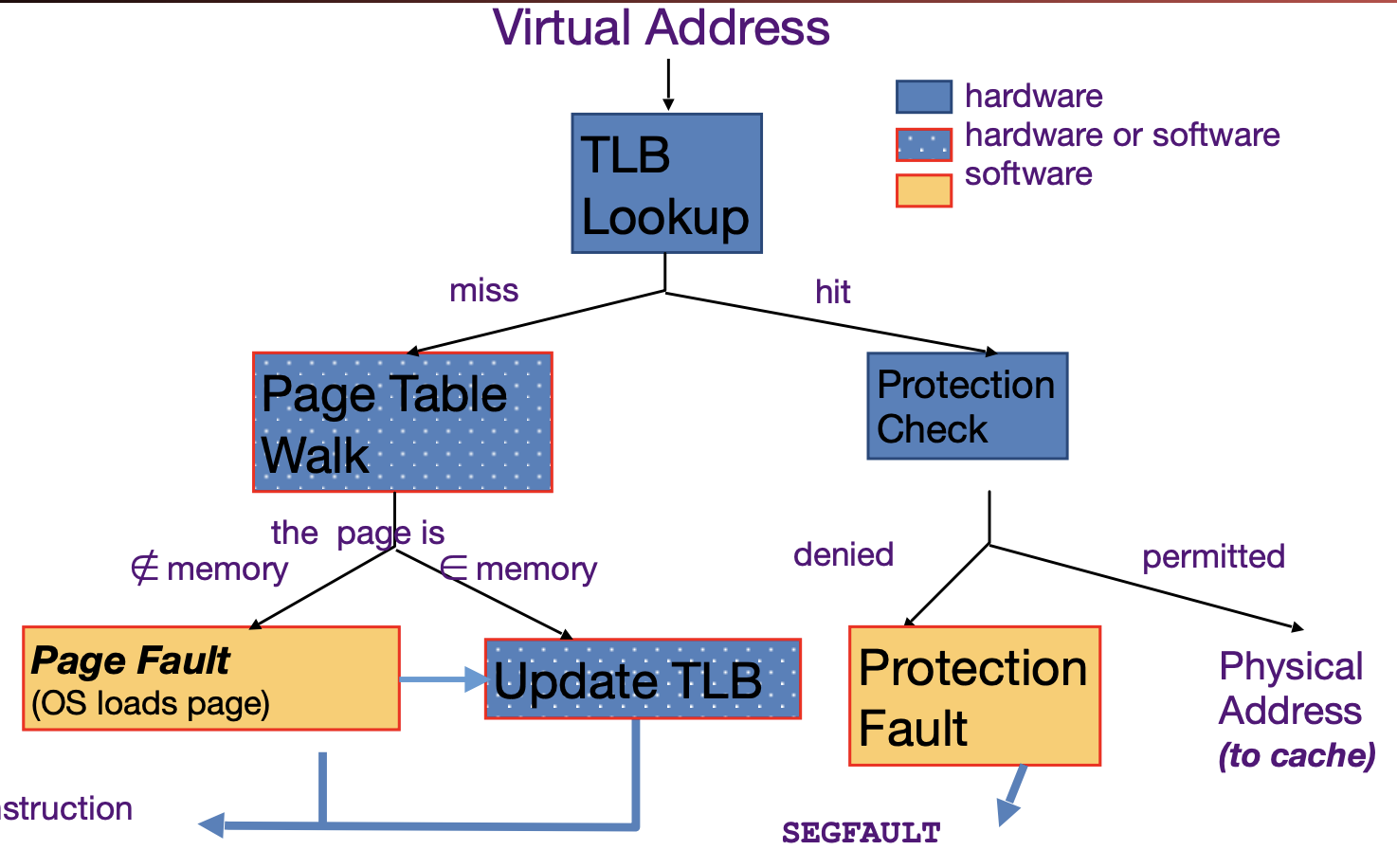

Virtual memory gives each program the illusion of a full memory address space. Dynamic address translation enables multiprocessing, location independence, and protection. A page table stores the physical addresses of the base of each page of memory. Each page table entry (PTE) has meta data and a physical page number, although it is often rounded up to guarantee alignment.

Page tables are kept in main memory. In the case of a page fault, a page is assigned in DRAM and disk memory, if it exists, is copied over. If no unused page is available, it is evicted with a write-back policy. A hierarchical page table can drastically reduce memory usage.

Translation lookaside buffers are caches for page tables. RISC-V has the hardware walk the page table whenever there’s a TLB miss and updates the TLB.

Once the working set exceeds physical memory, the system begins thrashing. Tricks like copy-on-write duplication and shared memory communication can save memory and time,.

Optimization

Amdahl’s Law

The amount of speedup is a function of the speedup portion $F$ and speedup $S$.

\[Speedup = \frac{1}{(1-F) + F/S}\]Parallel Processing

There are two appraoches to parallelism:

- Multiprogramming - run multiple independent programs in parallel.

- Parallel computing - run one program faster.

Single-Instruction/Multiple-Data Stream (SIMD) is one way to do parallel computing. Intel’s SIMD data types let you process 4 values at a time.

Unrolling

Unrolling can further improve performance by avoid pipeline hazards. Instead of processing one instruction per iteration, include multiple (e.g. 4) of the same instruction.

Blocking

Blocking can take better take advantage of the cache by performing operations on local values in a chunk. It’s often useful for subdividing matrices.

Multiprocessing

Multiprocessing involves multiple threads, which are sequential flows of instructions. Each thread accesses the same memory. Each core provides hardware threads, while operating systems multiplex software threads onto the hardware threads. Hardware multiprocessing involves multiple copies of PCs and registers. Multithreading improves utilization of existing processors while multicore involves duplicate processors that share an outer cache.

Threads can set off a data race if threads are accessing the same memory and at least one is writing. One solution is to lock access to a region, but two threads could both lock memory at the same time. One solution is read/write pairs, with load reserved and store conditional (only executes if the location hasn’t changed). An alternative is atomic memory operations, which store a duplicate of a value before performing an operation, letting the operation complete in a single step.

Deadlock is system state in which progress is impossible because everything is locked waiting for something else. Locks can help with limiting parallelism.

OpenMP is a langauge extension used for multi-threaded shared memory parallelism. The fork-join model creates a team of parallel threads that synchronize after they each compelte their instructions. Pragmas are the C preprocessor mechanism for langauge extensions.

#pragma omp parallel private {x}

{

/* code goes here */

}

Set number of threads with omp_set_num_threads(x);.

When working with a for loop, a reduction specifies that 1 or more variables that are private to each thread are subject of reduction operation at end of parallel region.

double avg, sum=0.0, A[MAX]; int i;

#pragma omp for reduction(+ : sum)

for (i = 0; i <= MAX ; i++) {sum += A[i];}

avg = sum/MAX;

MOESI

Multicores share a physical address space and coordinate/communicate through shared variables. Each CPU has a cache to improve performance. To keep caches coherent (agree on values), processors notify each other whenever they have cache misses or writes. Some blocks are shared, which can be represented as an additional bit. The states are:

- Modified: This cache has the only valid copy of the cache line, and has made changes to that copy.

- Owned: This cache is one of several with a valid copy of the cache line, but has the exclusive right to make changes to it—other caches may read but not write the cache line. When this cache changes data on the cache line, it must broadcast those changes to all other caches sharing the line. The introduction of the Owned state allows dirty sharing of data, i.e., a modified cache block can be moved around various caches without updating main memory. The cache line may be changed to the Modified state after invalidating all shared copies, or changed to the Shared state by writing the modifications back to main memory. Owned cache lines must respond to a snoop request with data.

- Exclusive: This cache has the only copy of the line, but the line is clean (unmodified).

- Shared: This line is one of several copies in the system. This cache does not have permission to modify the copy (another cache can be in the “owned” state). Other processors in the system may hold copies of the data in the Shared state, as well. Unlike the MESI protocol, a shared cache line may be dirty with respect to memory; if it is, some cache has a copy in the Owned state, and that cache is responsible for eventually updating main memory. If no cache hold the line in the Owned state, the memory copy is up to date. The cache line may not be written, but may be changed to the Exclusive or Modified state after invalidating all shared copies. (If the cache line was Owned before, the invalidate response will indicate this, and the state will become Modified, so the obligation to eventually write the data back to memory is not forgotten.) It may also be discarded (changed to the Invalid state) at any time. Shared cache lines may not respond to a snoop request with data.

- Invalid: This block is not valid; it must be fetched to satisfy any attempted access.

Dependability

Redundancy

3 types of digital design faults:

- Design Bugs: Mistakes in function, timing, power draw corrected at design time via testing.

- Manufacturing Defects: Impurities, breaking design rules, statistical variations, tested post-production.

- Runtime Failures: Hart faults like aging and soft faults like interference.

Redundancy in data centers, routes, disks, etc. to be fault tolorant; can be spatial (e.g. multiple risks) or temporal (e.g. rerunning code). Key dependability metrics:

- Reliability: Mean Time To Failure (MTTF)

- Service interruption: Mean Time To Repair (MTTR)

- Mean time between failures (MTBF)

- MTBF = MTTF + MTTR

- Availability = MTTF / (MTTF + MTTR)

- Annualized Failure Rate (AFR): Average failures per year

Error Detection

Memory accidentally flips bits, but error detection/correction codes (EDC/ECC) protect against failures. Extra bits at the end of each data-word detect faults. Parity bit adds a bit to each word to make it even, letting it detect any odd number of errors.

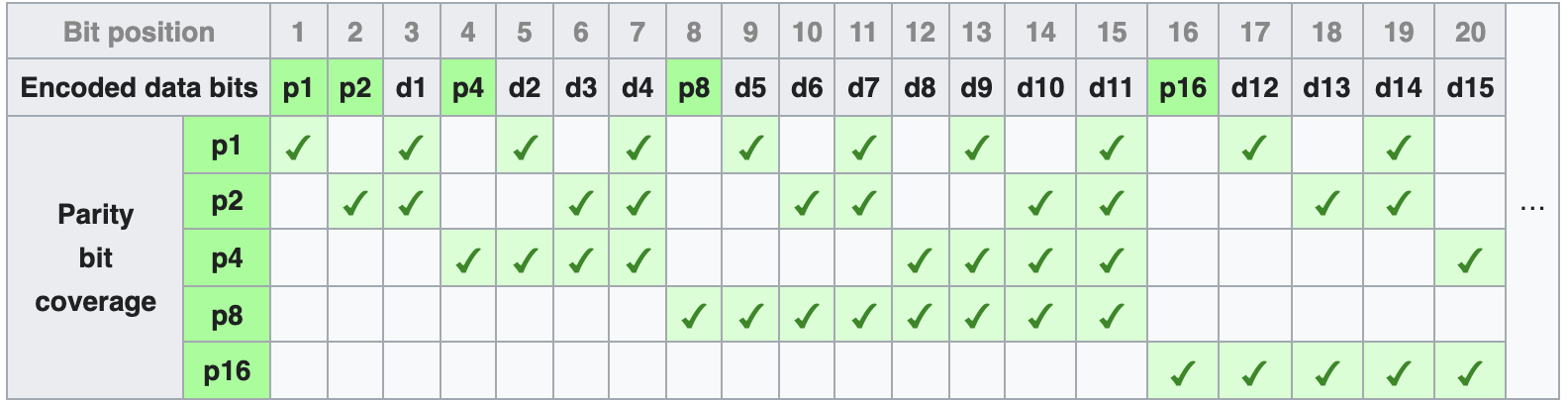

Error correction requires Hamming Codes, with the idea of finding the nearest valid code word. Hamming distance is the number of positions where words differ.

Parity bits occupy power-of-two bit positions. Extra bits can be added to detect additional errors.

RAID

Disks still have optimal storage density, so large projects usually deploy many disks. But, the MTTF decreases logistically with the number of disks:

\[\text{Combined MTTF} = \frac{\text{Single MTTF}}{\text{# Disks}}\]Redundant arrays of inexpensive disks (RAID) enables high availability, with 6 levels:

- No redundancy

- Duplicate disk

- Hamming code, with data disks and check disks to store Hamming code parity bits

- Drive disks each have a parity bit, so on failure, use other disks to find failure

- 3 but striped across blocks

- 4 but parity is interleaved

- 2 blocks for parity

Facts about RAID:

- “redundancy through parity” - 2, 3, 4, 5

- “a pro is having a small overhead” - 0, 2, 3

- “fast small reads are a pro” - 0, 1, 4

- “fast small writes are a pro” - 0, 1, 5

- “higher throughput is a pro” - 4, 5

- “parity is bit-striped” - 2

- “parity is byte-striped” - 3

- “parity is block-level striped” - 4, 5

- “disks play a part in increasing reliability” - 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Computing at Scale

Warehouse-scale computing (WSC) involves 1U servers in a rack of 40-80 servers with ethernet, switched in an array of racks with expensive switches. Energy efficiency is important and measured as total building power (e.g. AC) over IT equipment power (servers, networks). Cooling savings from water sources or open air.

Cloud computing is beneficial because of percieved isolation, low cost cycles, and elastic service. Cloud services can be SaaS, PaaS, or IaaS.

Request level parallelism: Load balancers direct traffic to clusters, which in turn select a server. Data level parallelism: Map reduce, where a master copy assigns map and reduce tasks to idle workers, e.g. Apache Hadoop and Spark. Only works for some problems and involves overhead.